/ Mar 07, 2026

Trending

In the early 1990s, Julia Donaldson was approached by a publisher who wanted to adapt one of her songs for the BBC. With the release of A Squash and a Squeeze, Donaldson published her first children’s book at the age of 45, igniting a career that resulted in modern classics like The Gruffalo, Room on the Broom, and Stick Man.

Donaldson had the edge over most first-time authors, in that she had a background in kids’ TV. But how does a regular person — one with no connections to the arts — become a published author? In this post, we’ll show you how to publish a children’s book and get it into the hands (and hearts) of young readers everywhere.

Knowing your audience is essential when you’re writing your book and crucial when you’re selling it. The first thing an editor wants to know is whether it’s the kind of book they can sell. Homing in on your book’s target audience will also help demonstrate your understanding of the publishing business, which is something most editors want in a collaborator.

Broadly speaking, children’s fiction is divided into four categories:

Modern editors take word count quite seriously. They rarely have time to thoroughly edit the books they acquire, so if you’ve written a 200,0000-word middle-grade opus, most editors will think, “Who needs that kind of stress?” and give it a hard pass.

If you want to learn more about writing for each category in children’s publishing, sign up for this free online course on Reedsy Learning.

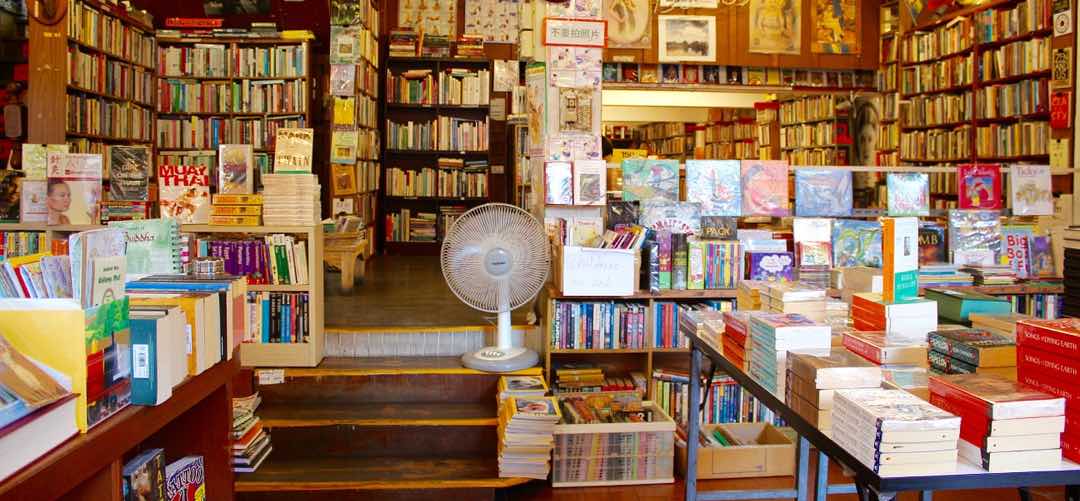

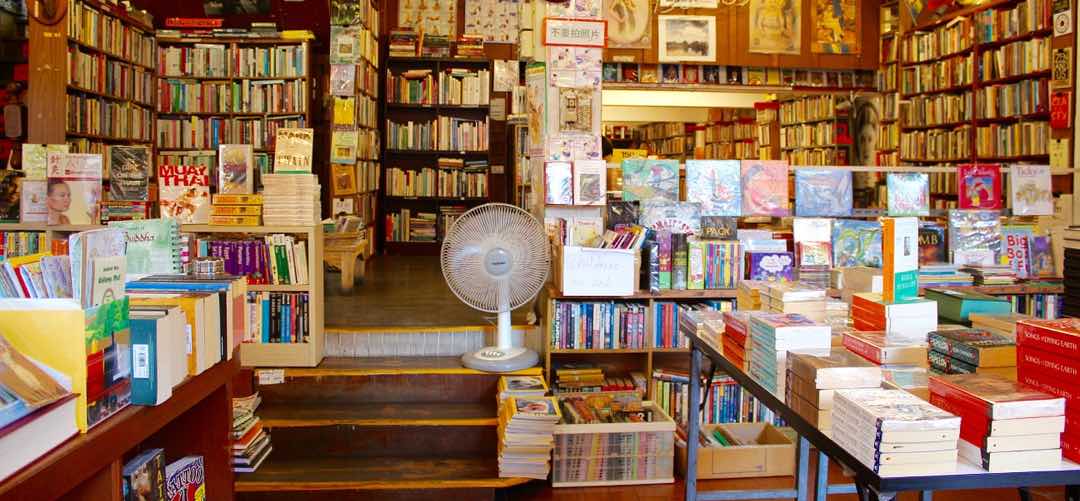

You want to see firsthand what bookstores are selling and promoting. Scanning Amazon’s Best Sellers list is fine, but going into a Barnes & Noble will give you a much better idea of ongoing trends. Brick and mortar stores still make up a large chunk of the children’s market and — more so than with adult books — most parents still prefer them over online retailers.

So put on your spy hat and go on an intelligence-gathering mission to the children’s section of a large bookstore. Locate the shelf where your book belongs (i.e., picture books, middle grade) and take notes on

You can easily scan through all the major titles in your category and find out which ones your book will compete with. In publishing, we often talk about “writing to market,” which naysayers interpret as “cynically imitating successful books.” But really, it’s about understanding the tastes of readers and publishers. You want to know what your audience has read before so you can either play to certain tropes or subvert them.

Tip: Sign up to the Children’s Bookshelf newsletter at Publisher’s Weekly to stay current with developments in the market (including the latest titles).

As we’ve mentioned, editors rarely have time to edit, so your manuscript needs to be as good as possible before you submit it.

Great books are almost always the result of meticulous, well-considered rewrites and edits. In a letter he wrote to his daughter, Roald Dahl revealed the all-consuming work that went into his classics:

“But I’ve got now to think of a really decent second half [for Matilda]. The present one will all be scrapped. Three months work gone out the window, but that’s the way it is. I must have rewritten Charlie [and the Chocolate Factory] five or six times all through and no one knows it.”

Work on your manuscript until you can’t possibly think of a way to improve it. Picture books and early readers are so short that it’s even more crucial than usual to perfect every single sentence. It may take less time to write a children’s book than it does to write a full novel, but that doesn’t mean it’s any easier! Whatever time you don’t spend writing, you should be thinking about your concept and how to make it better.

Many authors get their children (or nieces, or their friends’ children) to read their manuscripts. Kids are brutally honest, so they make for some of the best beta readers. Parents are also great for feedback — they’re the people who will actually buy your book, so their reactions can help you gauge whether the book is suitable for the market.

There are many excellent online communities where you can ask for feedback from fellow authors and enthusiastic readers. Facebook groups like Children’s Book Authors and Children’s Book Writers & Illustrators are a great place to start.

Put serious consideration into joining the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators. Members get access to a whole slate of resources like their “Book,” a page that includes directories of publishers, agents, and reviewers specific to children’s publishing.

SCBWI also has over 70 regional chapters around the world, allowing you to network with local, like-minded children’s authors. The annual fee is $80, but it’s well worth it — even if you only using a fraction of what they offer. Another group worth looking at is the Children’s Literature Association, which takes a more academic approach to children’s books, and can give you some great insights into what works and what doesn’t.

Joining a writers’ community can make all the difference in your burgeoning career. Once you’ve established yourself as an active and giving member, you will find it much easier to find beta readers or ask for a referral to an agent or publisher.

A professional editor doesn’t just improve your storytelling and fix your grammar — they also help you understand whether you’re writing for the right audience. Those with the proper experience will make sure your book adheres to the standards and unspoken rules of the trade, and often guide you through the process of submitting your manuscript.

Many freelance editors on Reedsy have worked for the world’s largest publishers, so they know precisely what acquiring editors are looking for. Their help can prove invaluable, so you should definitely consider getting a pro editor for your children’s book. You can learn more in this article about working with professional fiction editors.

Tip: Editing costs are often based on word count. Picture books and early readers are short, so a professional edit can be surprisingly affordable.

Unless you’re already a professional illustrator like Raymond Briggs (The Snowman) or Jon Klassen (I Want My Hat Back), don’t worry about illustrations. Don’t do it yourself, and don’t get your spouse, child, or college roommate to do it. Don’t even provide guidelines. The editor who buys your book will want to choose the illustrator — again, unless you are a pro illustrator who can do the job, submitting sketches or guidelines will only work to your disadvantage.

On the other hand, if you’re thinking about self-publishing your children’s book and curious about how much an illustrator may cost you, we recommend taking this quick 10-second quiz below that will give you an estimate based on real data.

The most straightforward way of selling to a publisher is to first secure a literary agent. According to Anna Bowles, a former commissioning editor at Hachette: “Publishers who accept unagented submissions are pretty rare nowadays.”

The great news for you is that we’ve already put together a list of 200+ veteran children’s book agents accepting queries and submissions! If you’ve no idea where to start, that list is a solid jumping-off point.

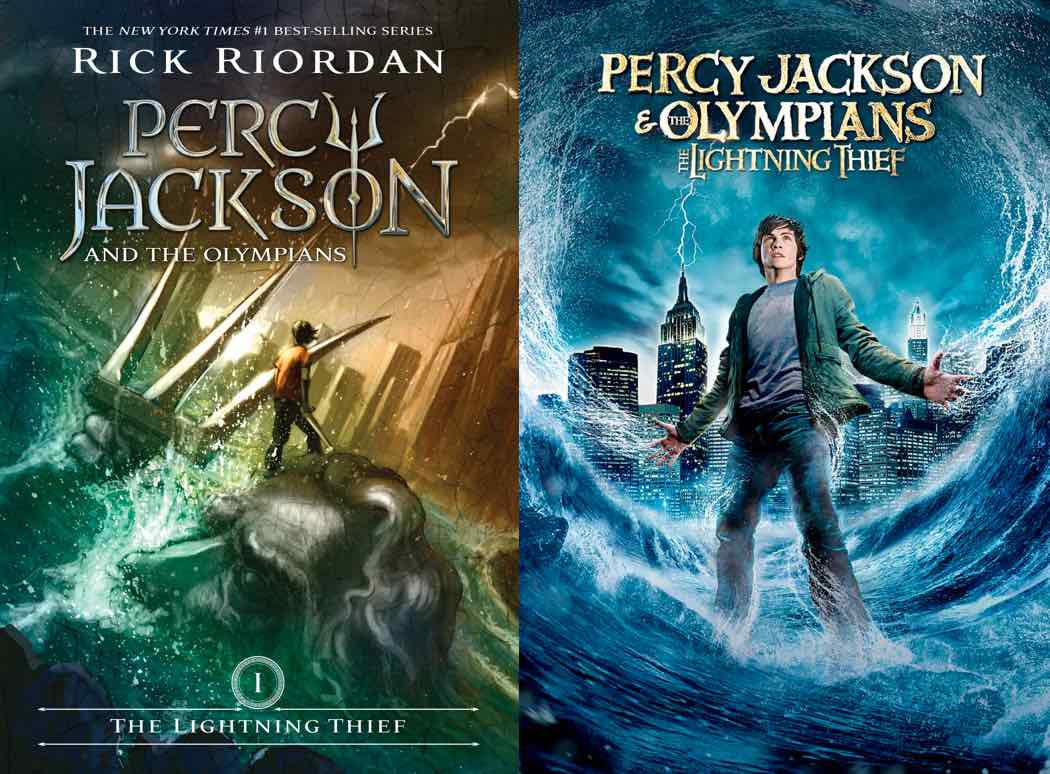

Now for a little more info on agents: an agent’s job is to sell your book to a publisher and negotiate the best deal on your behalf. If there’s the potential for your book to become the next Rainbow Magic or Percy Jackson, they will likely handle your film, TV, and merchandising rights as well.

A query letter for a children’s manuscript, even a picture book, is not so different from any other kind of fiction query letter. It’s a letter “querying” whether an agent is interested in representing you. Ideally, it is a one-page note with an “elevator pitch” that sells you and your book. It should succinctly explain

You want to make an impression. New writers will sometimes try to stand out by doing something crazy like filling the query letter envelope with glitter to show that they’re “young at heart” — but those guys are more likely to get arrested than represented.

We have plenty of tips for writing a great query letter, but here are two suggestions that will improve your chances.

If you do manage to catch an agent’s eye and they agree to represent you, you’re not on easy street just yet. Just ask J.K. Rowling, whose agent struggled to sell the first Harry Potter book until an editor finally took a chance on it.

But what happens if you don’t have an agent?

What if you’ve sent out a dozen perfect query letters and you’re still not getting the response you want? Well, you still have the option to submit the book yourself.

Without an agent, you need to search for publishers who accept “unagented submissions.” Depending on your territory, major publishers might accept unsolicited manuscripts. For example, Penguin Australia encourages children’s authors to submit directly while their US and UK offices claim to only accept submissions through agents.

Kick off your search with our list of 35 amazing children’s book publishers currently accepting submissions! From fiction to nonfiction, picture books to middle grade, you’ll surely find the perfect fit for your own beloved children’s book. But just in case you don’t, the following strategies can help.

It isn’t strictly true that the major presses won’t look at unsolicited manuscripts. Penguin actually has an imprint called Dial Books for Young Readers which lets authors submit directly. Likewise, at the time of writing, Clarion Books (an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) is also open to unagented authors. The small catch is, they won’t actually reply to an author unless they’re interested in publishing. So be ready for silent rejection!

Smaller independent publishers are more likely to show interest in unagented submissions. It’s just a matter of finding the right ones. The industry tomes Children’s Writer’s and Illustrator’s Market and Writers’ & Artists’ Yearbook (UK) both have directories that can help you find the right publishers. Likewise, members of the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators can access their exhaustive database.

For free resources, check out Picturebook Planet, which has a great list of picture book publishers you can submit to. For all other kid’s categories, the Published to Death blog has a substantial section in their publisher’s directory (scroll halfway down).

Many companies won’t take submissions all year round, but if you sign up for the free newsletter from Authors Publish, you’ll be notified when publishers start accepting direct submissions.

If a publisher wants you to pay to publish your book, just run away. The publishing landscape is infested with vanity presses, looking to prey on the dreams of inexperienced authors

It’s not about the money — it’s about the love of the craft, right?

Just kidding! Money always matters, especially if your goal is to write full-time.

Children’s authors can expect an advance of between $5,000 and $10,000 on their first book, with subsequent royalties of around 7% for printed books and up to 25% on ebook sales. Picture book royalties are split between the writer and the illustrator — and often in the illustrator’s favor.

Statistically, most published authors don’t make enough from their books to write full-time. If you see children’s publishing as an easy way to make big bucks, you’re setting yourself up for disappointment. But if you have an original idea for a story, the creativity to make it unique and enjoyable, and the drive to see it in the hand of your readers, then you can almost certainly get it published.

Now that you know the process behind traditional publishing, perhaps you’re curious about the alternative: indie publishing. It was once common perception to think of self-publishing as a last resort for authors who are unable to find a suitable publisher, but that’s no longer the case. To self-publish your children’s book is to retain creative control over your project and not have to wait for the decisions of traditional gatekeepers. It’s a faster path and with higher publishing certainty, albeit it requires a lot more work for the author.

Whether self-publishing your children’s book is better than traditional publishing is a question that has no definite answer — it comes down to you to examine the realities of both paths and see which one fits you best.

As we mentioned earlier, regardless of whether they’re self-publishing, children’s authors are expected to do a significant share of the marketing work. 80% of the time, marketing “kidlit” is the same as marketing any other book. There are dozens of great book marketing ideas for you to mine — from creating a mailing list to running promotions with other authors.

In this section, we’ll focus on the other 20%: the marketing techniques that are unique to children’s books.

Parents rely more on reviews when buying books for their children than when they’re doing it for themselves. They want to see what other parents think, how other children have enjoyed it, and whether the subject matter is appropriate for their own kids.

Even more so than with a self-published thriller or romance novel, a picture book with no reviews will really struggle to sell — and will be impossible to place in a library or bookstore.

Blogs, Instagram, Facebook Groups, Twitter, Reddit. These days, most parents of young kids are millennials. As a result, they will rely on the internet for almost any kind of recommendation (another generalization, admittedly).

Search through Facebook for children’s book groups, or groups that might be concerned with the topic of your book. If you’ve written a picture book about firetrucks, you can bet there’s a Facebook group of people (or people with kids) who love fire trucks.

Share pictures of your book on Instagram or Twitter using relevant hashtags — ones that either deal with your book’s topic (#unicorns #firetrucks) or tap directly into your audience (#mommylifestyle #picturebooksaremyjam).

You will have likely heard of the term “influencer,” most commonly used to describe YouTube or Instagram personalities who get paid by brands to promote products. While it’s not a bad idea to reach out of any of these people whose interests align with your book, remember that influencers come in many forms!

Yvonne Jones wrote a picture book about a monster truck (Lil’ Foot the Monster Truck) and to promote it, she reached out to Bob Chandler, creator of Bigfoot and originator of the monster truck sport. He liked the book and gave her a short review, which then helped get her foot in the door with various monster truck associations and blogs.

Similarly, if you can identify someone who has some clout amongst people who might buy your book, then politely reach out, introduce yourself and offer to send them a copy of your book.

Most schools will welcome visits from authors — in fact, some schools even set aside an annual budget for it. So why not get in touch with an administrator or a librarian and ask what you can do for them? And if you’re doing the school visit for free, Jones suggests taking the opportunity to sell some copies.

“Follow up your first email with a phone call to let them know that you visit local schools for free, in return for the school sending slips home, offering the chance to buy signed copies of the book.”

In the early 1990s, Julia Donaldson was approached by a publisher who wanted to adapt one of her songs for the BBC. With the release of A Squash and a Squeeze, Donaldson published her first children’s book at the age of 45, igniting a career that resulted in modern classics like The Gruffalo, Room on the Broom, and Stick Man.

Donaldson had the edge over most first-time authors, in that she had a background in kids’ TV. But how does a regular person — one with no connections to the arts — become a published author? In this post, we’ll show you how to publish a children’s book and get it into the hands (and hearts) of young readers everywhere.

Knowing your audience is essential when you’re writing your book and crucial when you’re selling it. The first thing an editor wants to know is whether it’s the kind of book they can sell. Homing in on your book’s target audience will also help demonstrate your understanding of the publishing business, which is something most editors want in a collaborator.

Broadly speaking, children’s fiction is divided into four categories:

Modern editors take word count quite seriously. They rarely have time to thoroughly edit the books they acquire, so if you’ve written a 200,0000-word middle-grade opus, most editors will think, “Who needs that kind of stress?” and give it a hard pass.

If you want to learn more about writing for each category in children’s publishing, sign up for this free online course on Reedsy Learning.

You want to see firsthand what bookstores are selling and promoting. Scanning Amazon’s Best Sellers list is fine, but going into a Barnes & Noble will give you a much better idea of ongoing trends. Brick and mortar stores still make up a large chunk of the children’s market and — more so than with adult books — most parents still prefer them over online retailers.

So put on your spy hat and go on an intelligence-gathering mission to the children’s section of a large bookstore. Locate the shelf where your book belongs (i.e., picture books, middle grade) and take notes on

You can easily scan through all the major titles in your category and find out which ones your book will compete with. In publishing, we often talk about “writing to market,” which naysayers interpret as “cynically imitating successful books.” But really, it’s about understanding the tastes of readers and publishers. You want to know what your audience has read before so you can either play to certain tropes or subvert them.

Tip: Sign up to the Children’s Bookshelf newsletter at Publisher’s Weekly to stay current with developments in the market (including the latest titles).

As we’ve mentioned, editors rarely have time to edit, so your manuscript needs to be as good as possible before you submit it.

Great books are almost always the result of meticulous, well-considered rewrites and edits. In a letter he wrote to his daughter, Roald Dahl revealed the all-consuming work that went into his classics:

“But I’ve got now to think of a really decent second half [for Matilda]. The present one will all be scrapped. Three months work gone out the window, but that’s the way it is. I must have rewritten Charlie [and the Chocolate Factory] five or six times all through and no one knows it.”

Work on your manuscript until you can’t possibly think of a way to improve it. Picture books and early readers are so short that it’s even more crucial than usual to perfect every single sentence. It may take less time to write a children’s book than it does to write a full novel, but that doesn’t mean it’s any easier! Whatever time you don’t spend writing, you should be thinking about your concept and how to make it better.

Many authors get their children (or nieces, or their friends’ children) to read their manuscripts. Kids are brutally honest, so they make for some of the best beta readers. Parents are also great for feedback — they’re the people who will actually buy your book, so their reactions can help you gauge whether the book is suitable for the market.

There are many excellent online communities where you can ask for feedback from fellow authors and enthusiastic readers. Facebook groups like Children’s Book Authors and Children’s Book Writers & Illustrators are a great place to start.

Put serious consideration into joining the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators. Members get access to a whole slate of resources like their “Book,” a page that includes directories of publishers, agents, and reviewers specific to children’s publishing.

SCBWI also has over 70 regional chapters around the world, allowing you to network with local, like-minded children’s authors. The annual fee is $80, but it’s well worth it — even if you only using a fraction of what they offer. Another group worth looking at is the Children’s Literature Association, which takes a more academic approach to children’s books, and can give you some great insights into what works and what doesn’t.

Joining a writers’ community can make all the difference in your burgeoning career. Once you’ve established yourself as an active and giving member, you will find it much easier to find beta readers or ask for a referral to an agent or publisher.

A professional editor doesn’t just improve your storytelling and fix your grammar — they also help you understand whether you’re writing for the right audience. Those with the proper experience will make sure your book adheres to the standards and unspoken rules of the trade, and often guide you through the process of submitting your manuscript.

Many freelance editors on Reedsy have worked for the world’s largest publishers, so they know precisely what acquiring editors are looking for. Their help can prove invaluable, so you should definitely consider getting a pro editor for your children’s book. You can learn more in this article about working with professional fiction editors.

Tip: Editing costs are often based on word count. Picture books and early readers are short, so a professional edit can be surprisingly affordable.

Unless you’re already a professional illustrator like Raymond Briggs (The Snowman) or Jon Klassen (I Want My Hat Back), don’t worry about illustrations. Don’t do it yourself, and don’t get your spouse, child, or college roommate to do it. Don’t even provide guidelines. The editor who buys your book will want to choose the illustrator — again, unless you are a pro illustrator who can do the job, submitting sketches or guidelines will only work to your disadvantage.

On the other hand, if you’re thinking about self-publishing your children’s book and curious about how much an illustrator may cost you, we recommend taking this quick 10-second quiz below that will give you an estimate based on real data.

The most straightforward way of selling to a publisher is to first secure a literary agent. According to Anna Bowles, a former commissioning editor at Hachette: “Publishers who accept unagented submissions are pretty rare nowadays.”

The great news for you is that we’ve already put together a list of 200+ veteran children’s book agents accepting queries and submissions! If you’ve no idea where to start, that list is a solid jumping-off point.

Now for a little more info on agents: an agent’s job is to sell your book to a publisher and negotiate the best deal on your behalf. If there’s the potential for your book to become the next Rainbow Magic or Percy Jackson, they will likely handle your film, TV, and merchandising rights as well.

A query letter for a children’s manuscript, even a picture book, is not so different from any other kind of fiction query letter. It’s a letter “querying” whether an agent is interested in representing you. Ideally, it is a one-page note with an “elevator pitch” that sells you and your book. It should succinctly explain

You want to make an impression. New writers will sometimes try to stand out by doing something crazy like filling the query letter envelope with glitter to show that they’re “young at heart” — but those guys are more likely to get arrested than represented.

We have plenty of tips for writing a great query letter, but here are two suggestions that will improve your chances.

If you do manage to catch an agent’s eye and they agree to represent you, you’re not on easy street just yet. Just ask J.K. Rowling, whose agent struggled to sell the first Harry Potter book until an editor finally took a chance on it.

But what happens if you don’t have an agent?

What if you’ve sent out a dozen perfect query letters and you’re still not getting the response you want? Well, you still have the option to submit the book yourself.

Without an agent, you need to search for publishers who accept “unagented submissions.” Depending on your territory, major publishers might accept unsolicited manuscripts. For example, Penguin Australia encourages children’s authors to submit directly while their US and UK offices claim to only accept submissions through agents.

Kick off your search with our list of 35 amazing children’s book publishers currently accepting submissions! From fiction to nonfiction, picture books to middle grade, you’ll surely find the perfect fit for your own beloved children’s book. But just in case you don’t, the following strategies can help.

It isn’t strictly true that the major presses won’t look at unsolicited manuscripts. Penguin actually has an imprint called Dial Books for Young Readers which lets authors submit directly. Likewise, at the time of writing, Clarion Books (an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) is also open to unagented authors. The small catch is, they won’t actually reply to an author unless they’re interested in publishing. So be ready for silent rejection!

Smaller independent publishers are more likely to show interest in unagented submissions. It’s just a matter of finding the right ones. The industry tomes Children’s Writer’s and Illustrator’s Market and Writers’ & Artists’ Yearbook (UK) both have directories that can help you find the right publishers. Likewise, members of the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators can access their exhaustive database.

For free resources, check out Picturebook Planet, which has a great list of picture book publishers you can submit to. For all other kid’s categories, the Published to Death blog has a substantial section in their publisher’s directory (scroll halfway down).

Many companies won’t take submissions all year round, but if you sign up for the free newsletter from Authors Publish, you’ll be notified when publishers start accepting direct submissions.

If a publisher wants you to pay to publish your book, just run away. The publishing landscape is infested with vanity presses, looking to prey on the dreams of inexperienced authors

It’s not about the money — it’s about the love of the craft, right?

Just kidding! Money always matters, especially if your goal is to write full-time.

Children’s authors can expect an advance of between $5,000 and $10,000 on their first book, with subsequent royalties of around 7% for printed books and up to 25% on ebook sales. Picture book royalties are split between the writer and the illustrator — and often in the illustrator’s favor.

Statistically, most published authors don’t make enough from their books to write full-time. If you see children’s publishing as an easy way to make big bucks, you’re setting yourself up for disappointment. But if you have an original idea for a story, the creativity to make it unique and enjoyable, and the drive to see it in the hand of your readers, then you can almost certainly get it published.

Now that you know the process behind traditional publishing, perhaps you’re curious about the alternative: indie publishing. It was once common perception to think of self-publishing as a last resort for authors who are unable to find a suitable publisher, but that’s no longer the case. To self-publish your children’s book is to retain creative control over your project and not have to wait for the decisions of traditional gatekeepers. It’s a faster path and with higher publishing certainty, albeit it requires a lot more work for the author.

Whether self-publishing your children’s book is better than traditional publishing is a question that has no definite answer — it comes down to you to examine the realities of both paths and see which one fits you best.

As we mentioned earlier, regardless of whether they’re self-publishing, children’s authors are expected to do a significant share of the marketing work. 80% of the time, marketing “kidlit” is the same as marketing any other book. There are dozens of great book marketing ideas for you to mine — from creating a mailing list to running promotions with other authors.

In this section, we’ll focus on the other 20%: the marketing techniques that are unique to children’s books.

Parents rely more on reviews when buying books for their children than when they’re doing it for themselves. They want to see what other parents think, how other children have enjoyed it, and whether the subject matter is appropriate for their own kids.

Even more so than with a self-published thriller or romance novel, a picture book with no reviews will really struggle to sell — and will be impossible to place in a library or bookstore.

Blogs, Instagram, Facebook Groups, Twitter, Reddit. These days, most parents of young kids are millennials. As a result, they will rely on the internet for almost any kind of recommendation (another generalization, admittedly).

Search through Facebook for children’s book groups, or groups that might be concerned with the topic of your book. If you’ve written a picture book about firetrucks, you can bet there’s a Facebook group of people (or people with kids) who love fire trucks.

Share pictures of your book on Instagram or Twitter using relevant hashtags — ones that either deal with your book’s topic (#unicorns #firetrucks) or tap directly into your audience (#mommylifestyle #picturebooksaremyjam).

You will have likely heard of the term “influencer,” most commonly used to describe YouTube or Instagram personalities who get paid by brands to promote products. While it’s not a bad idea to reach out of any of these people whose interests align with your book, remember that influencers come in many forms!

Yvonne Jones wrote a picture book about a monster truck (Lil’ Foot the Monster Truck) and to promote it, she reached out to Bob Chandler, creator of Bigfoot and originator of the monster truck sport. He liked the book and gave her a short review, which then helped get her foot in the door with various monster truck associations and blogs.

Similarly, if you can identify someone who has some clout amongst people who might buy your book, then politely reach out, introduce yourself and offer to send them a copy of your book.

Most schools will welcome visits from authors — in fact, some schools even set aside an annual budget for it. So why not get in touch with an administrator or a librarian and ask what you can do for them? And if you’re doing the school visit for free, Jones suggests taking the opportunity to sell some copies.

“Follow up your first email with a phone call to let them know that you visit local schools for free, in return for the school sending slips home, offering the chance to buy signed copies of the book.”

It is a long established fact that a reader will be distracted by the readable content of a page when looking at its layout. The point of using Lorem Ipsum is that it has a more-or-less normal distribution of letters, as opposed to using ‘Content here, content here’, making it look like readable English. Many desktop publishing packages and web page editors now use Lorem Ipsum as their default model text, and a search for ‘lorem ipsum’ will uncover many web sites still in their infancy.

It is a long established fact that a reader will be distracted by the readable content of a page when looking at its layout. The point of using Lorem Ipsum is that it has a more-or-less normal distribution of letters, as opposed to using ‘Content here, content here’, making it look like readable English. Many desktop publishing packages and web page editors now use Lorem Ipsum as their default model text, and a search for ‘lorem ipsum’ will uncover many web sites still in their infancy.

The point of using Lorem Ipsum is that it has a more-or-less normal distribution of letters, as opposed to using ‘Content here, content here’, making

The point of using Lorem Ipsum is that it has a more-or-less normal distribution of letters, as opposed to using ‘Content here, content here’, making it look like readable English. Many desktop publishing packages and web page editors now use Lorem Ipsum as their default model text, and a search for ‘lorem ipsum’ will uncover many web sites still in their infancy.

It is a long established fact that a reader will be distracted by the readable content of a page when looking at its layout. The point of using Lorem Ipsum is that it has a more-or-less normal distribution

Copyright BlazeThemes. 2023